How Afflecks went from quirky indie to part of a retail portfolio

‘If there ever is a sense for us where it’s become too corporate then maybe that’s time for us to hand it on’

By Mollie Simpson

On Saturday 19 January 2008, protesters gathered outside Afflecks Palace, shivering in the cold. Four teenagers with spiky hair, dressed in leather, denim and checked shirts on the edge of the kerb on Oldham Street, held a placard with the slogan “WE SUPPORT AFFLECK’S”. People passed around a petition titled: “Save Affleck’s Palace”.

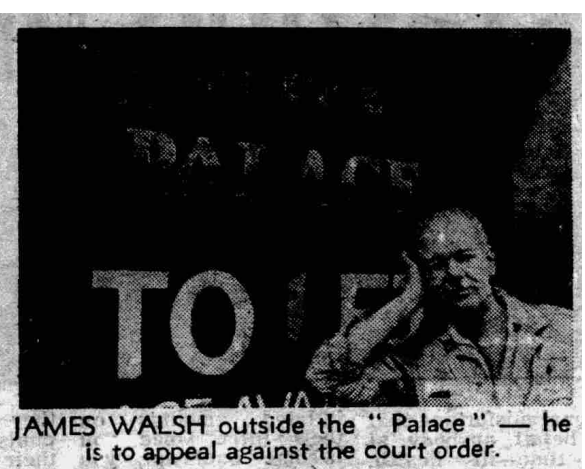

The protest took place at the height of discussions between Afflecks Palace’s founders, Elaine and James Walsh, and their landlord, the property firm Bruntwood, over Bruntwood’s decision not to renew their lease. The battle between a quirky, independent retail bazaar and a property developer captured Manchester’s imagination. Eight thousand people signed the petition to keep Afflecks alive, and the online forum Skyscraper City was alight with conspiracists suggesting that Bruntwoods wanted to turn the building into flats.

That impression changed on 16 January 2008, when the Manchester Evening News reported that Elaine Walsh “snubbed” a meeting with Bruntwood intended to discuss an offer of a new lease. A counternarrative took hold: Elaine was the one putting stallholders’ livelihoods at risk by allowing the situation to remain uncertain. “It would help if the lease-holder and Afflecks’ founder, Elaine Walsh, started telling people exactly what she intends rather than increasing doubt by using go-betweens in the form of representatives,” Manchester Confidential wrote that same month in a since-disappeared article, accessed via Skyscraper City. “She should make it crystal clear whether she wants to carry on with Afflecks or pull out and let the place and the 300 jobs associated with it — go.”

By the end of that month, the story was not about survival, but ownership. Bruntwood had another offer for Elaine Walsh: they wanted to buy Afflecks Palace and run it themselves with new management.

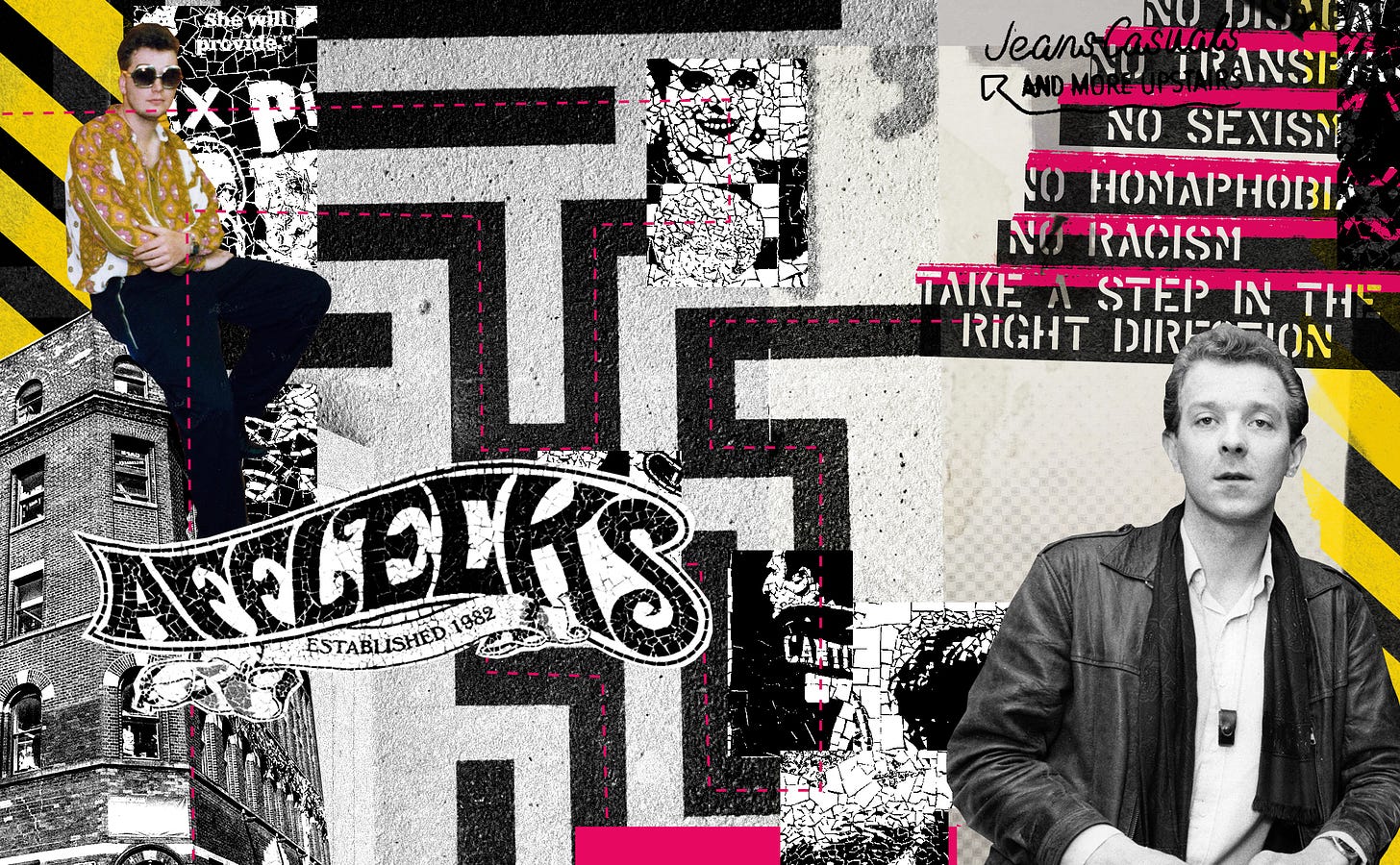

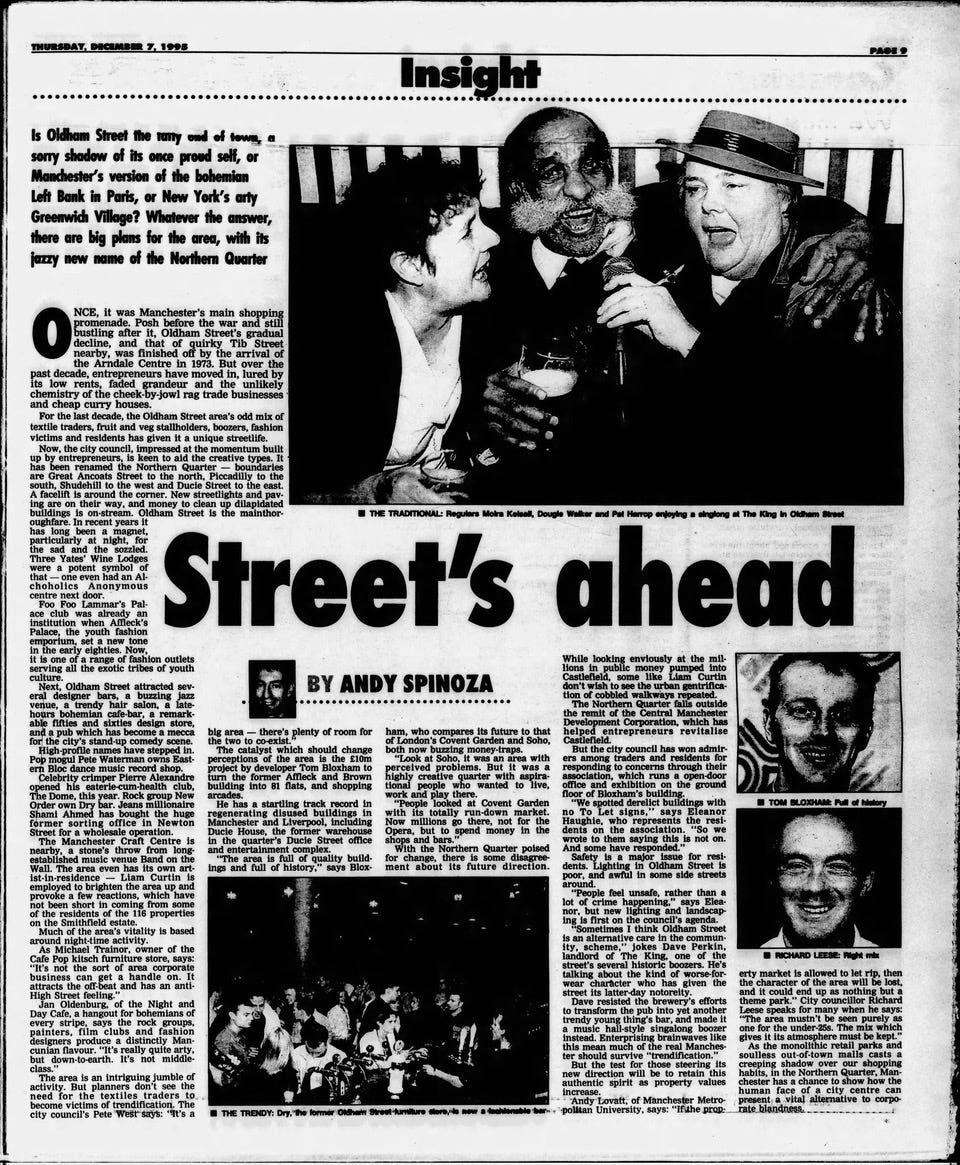

Elaine and James Walsh — “two eccentric hippies”, in the words of their friend Leo Stanley — imagined Afflecks as both a place to support youth culture and entrepreneurship, and a haven for those on the fringes. The result, as Andy Spinoza writes in Manchester Unspun, is that it became the centre of the Madchester revolution, “the mecca for new fashion trends” that sold to “the growing numbers of backpacking and sofa-surfing youngsters for the street life, gigs and the chance to meet the bands in the Northern Quarter clubs and bars”.

Afflecks, of course, survived the transfer of ownership and still exists today. Does it still serve the same role to the community as it did when its radical mission first began? 16 years on, people are still divided as to whether it was right for a property developer to reap the benefits of a business that Elaine and James had created — and whether they’d made the place too corporate in the process. There are Elaine’s friends, who accuse Bruntwood of making Afflecks “commercial” — a place where stallholders “sell to tourists” — and then there’s Bruntwood’s side, whose CEO Chris Oglesby says, “If there ever is a sense for us where it’s become too corporate, then maybe that’s time for us to hand it on.”

The long saga of Afflecks spans four decades, two missing Banksys, plenty of “vulgar tat”, Manchester’s gangster culture and even more arcane disputes with the council over market licences. But I wanted to find out what Afflecks means to people today, and get under the skin of a Manchester institution.

Origins

After the Arndale Centre opened in 1979, the shops on Oldham Street emptied out and the area fell into decline. The department store Affleck & Brown, on the corner of Oldham and Tib Street, had been vacant and unoccupied since 1973. On 6 September 1982, an article in the Manchester Evening News advertised “an emporium for everything from antiques to designer clothes”. James Walsh, 53, and Elaine Williams, 34, had taken out a 25-year lease on the building from Michael Oglesby, the Lincolnshire property developer who founded Bruntwood by buying derelict factories and vacant department stores.

“People particularly like Tib Street and the old-fashioned clutter of shops,” James told the Manchester Evening News. “The building is marvellous for what I want because it has a certain dilapidated splendour.” He encouraged as many people as possible to come and shop in the new Affleck’s Palace.

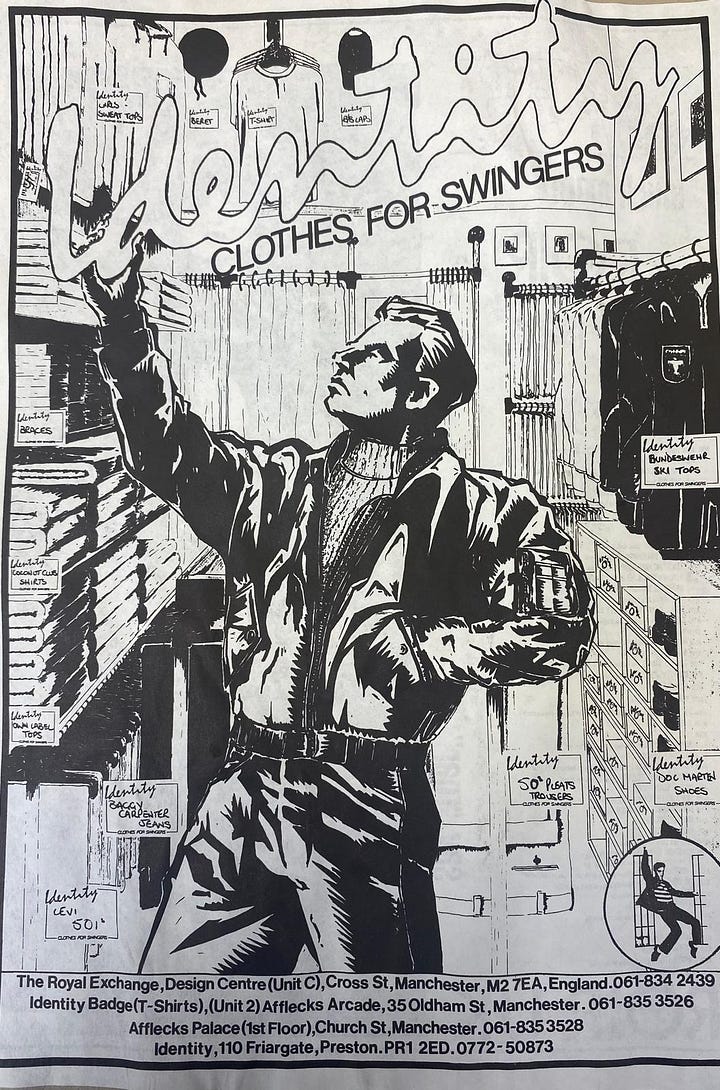

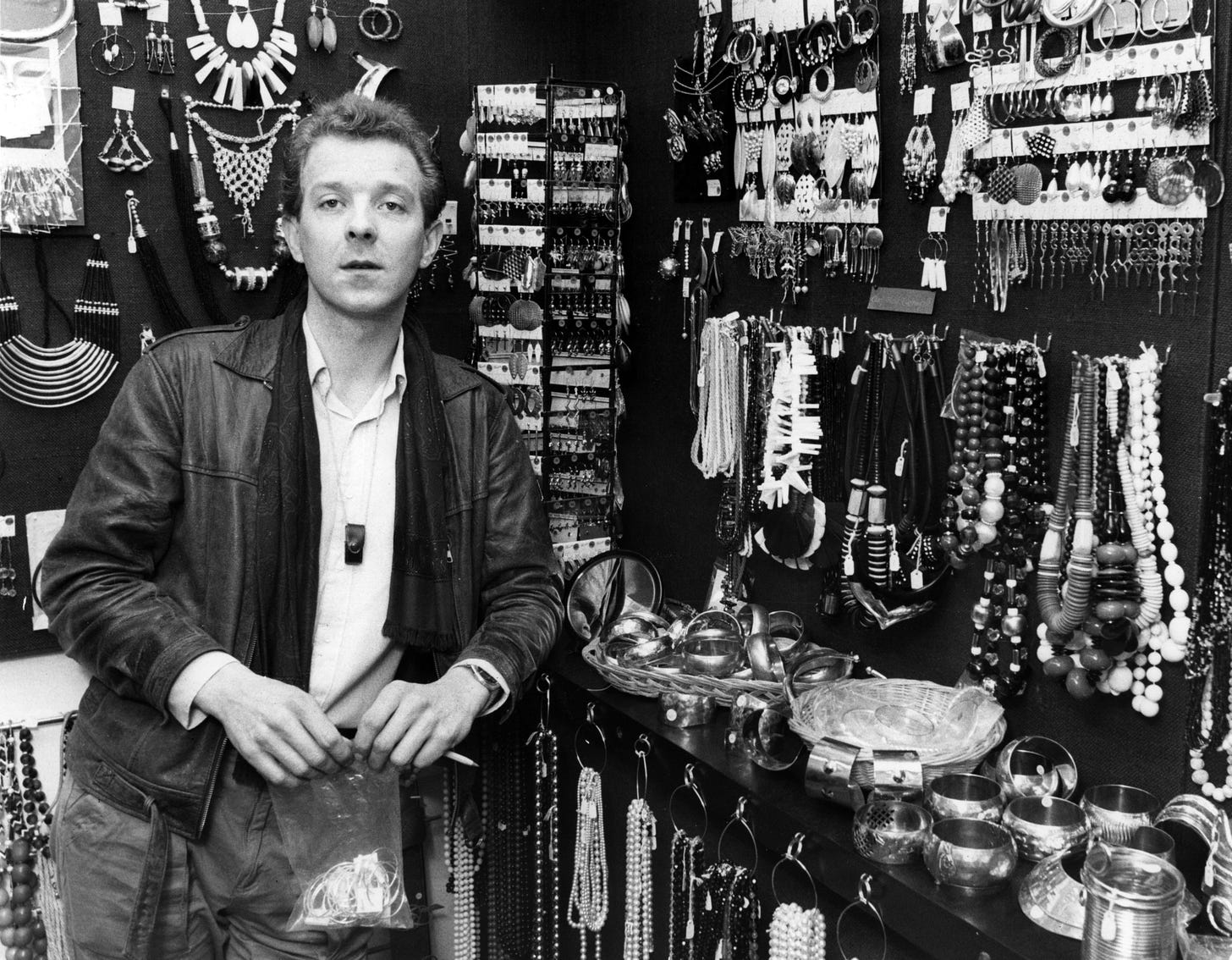

Thousands answered the call. Leo Stanley, a young, working-class lapsed Catholic who ran a stall called Identity, designed t-shirts emblazoned with provocative slogans that made their way into the famous Hacienda. He came up with the iconic slogan, “And on the sixth day God created Manchester”. Soon, he was selling 500 t-shirts a week. “I have no regrets, because I had the best cocaine, the fastest cars and the most expensive prostitutes, and that’s where the money went,” he says.

Simon Calderbank, who worked at Wayne Hemingway’s alternative clothing shop Red or Dead between 1989 and 1993, remembers a familiar but thrilling routine: arriving late for the start of his shift, getting fined for tardiness by the manager Dave Williams (who ran Afflecks “with an iron rod”), eating “stodge hangover food” from a sandwich shop and sinking a pint at Dry Bar on his lunch break. Then The Millstone for drinks after work, filled with a “wild crowd” of “punks, mods and oddbods”. “People would say ‘Get a job in the Corn Exchange’ and we were like, what for?” he says. “It’s up its arse, it’s posh down there. People would look down on Afflecks because it was dark, it smelled, it was weird. But it was ours.”

Damian Morgan, who worked for Identity between 1987 and 1991, lived on Barlow Moor Road in Chorlton with other stallholders, which became known as the Afflecks party house. “I don’t remember having a meal at any point for about three years,” he says. Morgan’s job was to test the popularity of Stanley’s ideas: wearing his new t-shirt designs at the Hacienda and noticing how the crowd responded. “And whichever one went down best would get printed,” he says.

He had been a shy teenager, but hanging out with the era’s famous bands at Affleck’s Palace made him realise that stars like Ian Brown, Peter Hook and Bez “were just normal human beings”. Morgan later went on to represent members of The Happy Mondays, The Smiths, Oasis and The Specials as a public appearance agent.

Not everyone was blessed with immediate success. Ed Barton, a composer and artist, was a stallholder in the late 1980s. He says he “started really, really badly” and sold absolutely nothing during his first five weeks. “I went to London and went to about five wholesalers and bought what, frankly, the rest of the world perceived as vulgar tat and displayed it in my stall quite badly,” he says. Matthew Norman, a close friend, recalls his other experiment, where Barton put “a goal against the wall and you’d pay 50p for kick the ball into the wall three times”.

Soon, his colleagues started a sweepstake on how long he was going to last. “Which I wish I’d joined, because then I would have made some money,” he says. But it turned out okay, eventually. An idea popped into his head, “which was some fish. And I put the fish on a t-shirt and that sold. And some more people came in and said ‘Are there any more fish on shirts?’ And then it was selling all around the country and festivals and Europe.”

Barton eventually abandoned that stall when he got fed up of being “sat at home with tippex and photos and photocopiers cutting up photos of fish”, but he still holds an affection for his time there. Afflecks played an “accidental, ancillary function” in supporting “a lot of secondary people” in life, he says. “My friend Pat being the example. He wasn’t terribly good at the world. His tea was paid for by his girlfriend.”

Pat, a talented pavement artist who couldn’t work out how to make money, picked up work at various stalls at Affleck’s Palace from friends who looked out for him, and ended up okay. In 1985, the Manchester Evening News wrote, “The majority of the stallholders are young and previously unemployed, many of their customers are also young and still unemployed. But for the last four years Affleck’s Palace has offered an intriguing mixture of off-beat fashion and fun shopping at the kind of prices we can all afford.”

“The people who were employed there were more important than the people that were sold to there,” Barton says. “It was a lot of hopeful artistic people it was helping support.”

The Banksys

Elaine Walsh didn’t reply to my initial request for a comment on this story. A neighbour kindly offered to ask her in person on my behalf, but I was told she didn’t want to talk as it was “too painful”. She would later message me directly on Facebook and wish me luck with the story, but didn’t respond to further questions.

By all accounts, James and Elaine were both well-loved fixtures in Afflecks. “I don’t care what anyone says, James and Elaine were the start of the Northern Quarter,” Leo Stanley says. “Don’t let anybody tell you anything else.” Calderbank says they occupied paternal roles in Afflecks, kindly watching over struggling young entrepreneurs and making sure they could always pick up work helping at other stalls or painting walls when their ideas weren’t working out. Elaine also had an anti-establishment streak.

There’s a myth about Afflecks that I’ve struggled to unpick. It’s said that in the early days, Elaine placed two relief boards on the outside walls of the building, near the Tib Street entrance. The next day, two Banksy artworks had been painted on them, sparking rumours that Elaine and Banksy knew each other.

What happened next is disputed. “I think they binned them or painted over him or redid it with emulsion,” Stanley says. But according to the photographer Mary McQuillan, the Banksys were covered with “dingy old perspex” to protect them, and over the years, as the wall became plastered with posters advertising nights out, the top of the Banksys were just about visible, “lurking beneath” layers of paper. Then at some point, they disappeared from view. Banksy’s representatives didn’t respond to this story.

By the time the lease expired in 2007, Afflecks had survived a number of existential threats. A major fire in 1989 destroyed all the clothes and melted the rubber soles of the Doc Martens in Red or Dead, a blow from which Tom Baxter Tiffin, a neighbouring stallholder who ran a magazine and t-shirt shop on the top floor, never recovered. “It basically put an end to my business,” he says, recalling an insurance payout that barely covered his losses. In the 1990s, as gangs from Cheetham Hill moved into the city centre, the atmosphere felt less euphoric and became more associated with “a lot of horribleness and nastiness and shoplifting, fighting, intimidation, police surveillance”, in the words of Stanley.

When Elaine entered negotiations with Bruntwood, she was running a vintage shop, a Victorian fetish shop, and a fancy dress shop in Affleck’s Palace, plus, the livelihoods of 300 people were resting on her shoulders. The building was increasingly in need of repair, too, with issues over the roof and a question mark over who was liable for fixing it. At one point, James was said to have told Elaine: “Let’s just bring this to an end. Stop battling and spending money.”

Then, in January 2008, Chris Oglesby had another offer for Elaine Walsh. He was willing to buy the business from her and run it with new management. Elaine told a friend: “I’m tired”. If selling Afflecks was the only way to ensure it survived, she wanted to know how much she could get.

Enter Tony Martin

In January 2008, Bruntwood CEO Chris Oglesby had an offer for Tony Martin, who had worked for Bruntwood since 2007 as the manager of Manchester Technology Centre, an office block on Oxford Road. “We’re in a situation,” Oglesby is said to have told Martin. “You’ve seen the bad press around Bruntwood. We want to be seen as the people who are absolutely going to continue Afflecks on its journey, and we want someone good managing it.”

Martin recognised this was an unbelievable offer, but he had reservations. He was aware of the rumours that Bruntwood was going to close Afflecks down and thought that the narrative making his employer out to be the bad guy was unfair. “I remember feeling quite bitter towards Afflecks,” he says.

This wasn’t always the case. Afflecks had been there throughout his life, including when he was a teenager questioning his sexuality in the early ‘80s, heading to the record shops and t-shirt stalls in Afflecks for refuge when people at school asked him “So, are you a boy or are you a girl?”

“That was something that never got questioned in Afflecks,” he says. “I could walk in there and would never have people questioning how I chose to be.”

“We just want the bad press to back off and not be seen as the bad guys,” Oglesby told Martin. Martin considered it, but he had one condition. “I want to do it on my own terms and not have corporate involvement,” he says he told Oglesby. It was important that stallholders, some of whom had been there since 1982, like Vanessa from the fancy dress shop American Graffiti, knew that Afflecks was going to be safe in his hands. Oglesby agreed.

“It felt like the right thing to do,” Oglesby says, speaking to me over the phone. “Afflecks is such a wonderful institution.” He acknowledges that buying Afflecks was a decision that went against his own business instincts and forced him to appeal to his emotional side: “Hard-nosed and commercially, the best thing to do with it would’ve been to see the building emptied and convert it into apartments. But we felt it was too important.”

‘What you have started here will continue’

What was Affleck’s Palace going to be like under the control of a property firm? Many had grown to see the move as a divorce between past and present – a shock to Manchester’s cultural scene, from which it might not recover.

But in the end, the greatest shock was how much stayed the same. On 31 March 2008, Affleck’s Palace ceased trading and on 1 April, Elaine handed over the keys and the building reopened as just Afflecks. Tony Martin chose to keep the fetish shops and the piercing parlours and the shops selling t-shirts emblazoned with ageing indie rockers. Martin says he made a promise to Elaine that he wanted to honour. “What you have started here, we will continue,” he recalls telling her at the time. “It’s a legacy we will continue in your name.” Everyone I interviewed has positive things to say about him.

If anything, Afflecks started to thrive again. Martin released money to fix the building and repaired the roof and the rendering. Within a few years, it went from 25% occupancy to completely full, with Martin having to turn prospective traders away.

Elaine Walsh disappeared soon after. Her husband James passed away after a long period of illness, and at the funeral in Prestbury, she got the chance to reconnect with old faces from Afflecks one more time. “I just said to her, look, I’m sorry the way it’s worked out, and thank you for everything you’ve done,” Leo Stanley says. “She said, no problem, and then she just disappeared.”

On 19 May 2016, a story about Ibiza’s thriving vintage fashion scene appeared in The Guardian after the writer discovered a shop called Vintage Icons and Echoes in Saint Eulalia, a laid-back part of the island with a thriving nightlife scene. The writer described the shop as “an Aladdin’s cave of clothes, artefacts and designer bargains”. The language almost exactly mirrors how Affleck’s Palace was described by the Manchester Evening News in 2007 — an “Aladdin’s cave of kitsch treasures”.

The owner was a British woman called Elaine Walsh, who explained that she was the founder of Affleck’s Palace in Manchester, until “issues with the lease… forced her to give it up”.

“It’s just a fun shop. It’s not meant to be serious, and I wanted it to be affordable,” Elaine told the Guardian at the time. “People find it amusing and there’s always something new. I’m constantly introducing and removing pieces — it’s a bit like gardening!”

Two of her friends, Garry and Leo Stanley, say they understand why it’s still painful for Elaine to talk about Afflecks. She’s said to have walked away from Afflecks with a million pounds, no dilapidations bills and the two Banksys, though we’ve been unable to confirm this either way. Bruntwood chose not to speak to these details, instead referring me to a statement from Chris Oglesby:

“In 2008 when the future of Afflecks looked uncertain, we knew that it was too important to lose. Since then we have worked hard to ensure this iconic retail destination remains open, inclusive and a place where independent businesses can experiment and thrive — no matter how alternative the idea!

Manchester's cultural landscape would be much depleted without Afflecks and that is why we remain custodians of this incredible community. Over the last 16 years, we’ve nurtured a home for independent traders, makers and creators in the Northern Quarter. We are proud to see the millions of Mancunians and visitors pass through Afflecks every year (1.1 million so far in 2024) providing a safe space where everyone is welcome.

As we look to the next 40 years, our commitment to Afflecks and the community it serves is stronger than ever, and we’re proud to see it continue as a place where everyone can feel seen, accepted and celebrated.”

Today, Elaine and James Walsh are scarcely mentioned, though that might have something to do with their tendency to avoid the limelight. In a coffee-table book published in honour of Afflecks’ 40th anniversary, commissioned by Bruntwood and edited by Jonathan Schofield, they’re named in the introduction as the “first careful custodians” who created “a brave venture in a difficult time”. Leo Stanley asked me to make sure their hard work was credited in this piece. “I do hope you give them a good mention,” he told me.

Tony Martin left Bruntwood in September 2020, after 12 years managing Afflecks and, later, Oxford Road’s Hatch, which was inspired by Afflecks and designed to support Afflecks stallholders who wanted to take the next step but weren’t yet ready to open a shop on the high street. He tells me that on the side of the building of Afflecks, there’s a silver tree with swirling roots and branches that spiral off in various directions. Martin commissioned the piece when he became manager, in honour of Elaine and James. The couple are the roots of the tree, while the branches represent the businesses that have grown there and everything since. The poison ivy twisting around the branches represents Afflecks. “A lot of people don’t realise the story behind that,” Martin says. “And that’s probably what upsets me now, that things like that have been forgotten.”

Amazing article. Deep dive, Manchester centric. More like this. (I mean, everything The Mill does is great, but I liked this one a lot!)

I have some great memories of Affleck's which will probably be with forever. Used to love the buzz of making my way up the stairs following my ears in search of the heavy bass coming out of speakers in Fat City records' shop. Then searching for new import CDs and vinyl, knowing that they were at least two weeks ahead of HMV. Intoxicating.