The police weren't looking for a serial killer — but suddenly I was

Did multiple loving marriages in the North West really end in murder-suicide?

This weekend’s story is by David Collins, the Northern Editor of the Sunday Times, a long-time Mill subscriber and the author of a thrilling new book, The Hunt For The Silver Killer. Just a quick warning, this piece contains descriptions of graphic violence and suicide.

By David Collins

It was love at first sight when Michael and Violet Higgins met in a Manchester dance hall in 1968. They married just one year later and enjoyed 30 years of happy marriage.

It’s said that on February 21, 2000, Michael went on a murderous rampage around their semi-detached home in a broad, leafy Didsbury street. He is said to have battered Violet, then stepped away from her corpse to stab himself in the throat and choke himself with a coat hanger. The police concluded it was a murder-suicide committed by Michael.

Michael was 18 years younger than his wife. Violet was 76 years old when she died, a retired constable with Greater Manchester Police. Michael's family never believed he could have been capable of such a crime: he was gentle and loving with Violet, and besides, his brother told me, he had advanced Parkinson’s disease, which affected his co-ordination. Michael struggled to make a cup of tea in the morning, never mind carry out a murder. Still, detectives believed Violet was talking to friends and family about placing Michael in a care home due to his Parkinson's disease, which may have triggered the murder.

That would have been the end of the matter. Except, 20 years later, the senior coroner’s officer for Cheshire Police, Stephanie Davies, would write a confidential report which linked their killings to the murder-suicides of two other elderly couples, just down the road in Wilmslow, Cheshire.

Davies’s highly sensitive report – submitted to Cheshire Police’s major incident team in 2020 – raised the spectre that a killer might be on the loose. Her review of the murder-suicides, known colloquially inside the constabulary as the “Davies Review”, raised concerns about a man with advanced Parkinson's disease being capable of such a murder.

“The key concerns highlighted with this case are: Mr Higgins had a history of Parkinson’s disease. Did he have the strength, co-ordination and dexterity to carry out the sustained and violent attack on his wife?” Davies wrote.

It questions whether he would be able to twist a wire coat hanger about his neck after stabbing himself in the throat — which is the version of events offered by Greater Manchester Police to the coroner at the inquest. “The combined methods of sharp-force injury to the throat, the pills thrown on the floor, and the twisting of the coat hanger around the neck all in combination strikes as a very rare and unusual suicide method,” Davies's report reads.

“These methods and signs of suicide could therefore be indicative of exaggeration at the scene.” In other words, it could indicate where an offender is trying to make obvious to police that the death was from suicide, rather than a disguised murder.

Certainly, this version of events would make more sense to Michael’s brother, Daniel, and his sister Betty, who knew him as a “kind, gentle and intelligent man” who was devoted in every way to his wife Violet.

The Davies Review

The question Michael and Violet Higgins's case raises is an obvious one. How does a man who struggles with the everyday functions of life get blamed for murder? Was it possible that Michael was the killer? Or — as the family said — was he simply incapable of the crime?

It is a puzzle I have been trying to solve ever since I received a telephone call while in my shed at the bottom of the garden in April 2020, in the midst of the first national coronavirus lockdown.

The call was from a source in possession of a confidential report by Stephanie Davies, the senior coroner’s officer for Cheshire Police. Davies was a high-flyer. She had been given two commendations by the chief constable and held a string of qualifications in death investigations, crime scenes and forensic science. She led a team of thirteen civilian staff investigating sudden and unexpected deaths in the county of Cheshire.

Her 179-page review focused on two murder-suicides in Wilmslow, Cheshire, which took place in 1996 and 1999, just a few streets apart from one another.

Both cases involved elderly couples with no history of domestic violence, health problems, financial worries or serious family issues at the time of their deaths. There was no motive for either husband, nor a shred of evidence that had ever existed to suggest why they might have become murderers overnight. They lived in large houses in one of the wealthiest areas outside London: a town where footballers and soap stars rub shoulders with businessmen and bankers, and violent crime is a rarity.

I read the Davies Review in one sitting. The graphic violence of the crimes was disturbing. Photographs of married couples lying side by side in twisted, bloodied bedsheets. The women, in particular, had been the focus of excessive violence: bludgeoned and stabbed, wounds far in excess of what was required to kill.

In each case, the police had concluded the killer was the husband, who had subsequently taken his own life. But Davies believed the two murder-suicides in Wilmslow were actually the work of the same offender.

Serial killers are rare creatures. Rare enough that their names live on in public consciousness long after their crimes. Peter Sutcliffe. Ian Brady. Fred West. They are the bogeymen. The reason we listen out for the creak on the stairs.

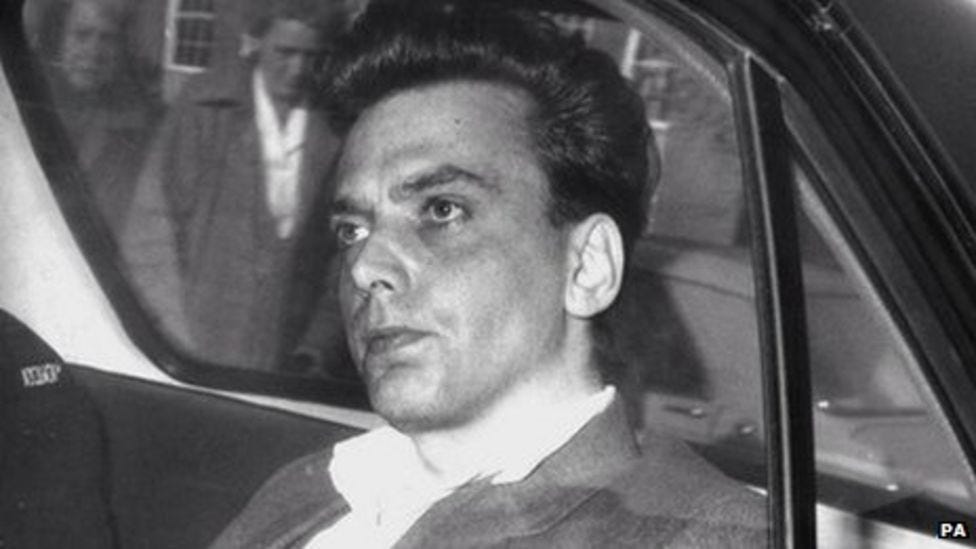

I have only had direct contact with such an individual once during my 17 years as a reporter. His name was Levi Bellfield. He specialised in attacks on young women, using a heavy blunt object to batter them about the head in a flurry of hatred.

I interviewed him when I was a cub reporter and I remain the only journalist who has ever spoken to Bellfield. As a young man, I entered his inner circle. I spent time with his friends and family in the bars and pubs of south west London, drinking with them in dingy pool halls and houses littered with beer cans. It was a dark world, inhabited by car clampers and sex offenders. Women were spoken about as if they were a disposable commodity.

Eventually, Bellfield would grant me an interview. At the time, he was the prime suspect for the murder of Milly Dowler, a schoolgirl who vanished from Walton-on-Thames in Surrey in March 2002. During my interview, Bellfield admitted to driving a red Daewoo car caught on CCTV shortly after Milly went missing.

The admission placed him at the scene of Milly’s disappearance, and in the words of the lead detective "raised the evidence against him to the next level". Two years later, he was convicted at the Old Bailey.

During that period, I received death threats from Bellfield’s cronies. “We’re going to find you and bury you next to Milly,” said one whispered message left on my voicemail one evening. I spent months looking over my shoulder, expecting a revenge attack.

None came. But it reminded me of the types of people I had been dealing with on a daily basis. People who would think nothing of inflicting violence upon a reporter they felt had betrayed one of their own, even if that man was in jail for multiple murders. I changed my phone and my number, and moved on to report on other stories.

A new type of killer

Bellfield was cunning. But not so cunning he avoided capture. The Davies Review seemed to detail the work of an entirely different breed of killer. For years, this person existed only on paper and in the canteen gossip of Macclesfield Police Station.

Their crimes were stored in a dusty box marked “Special Interest”, kept inside a locked cupboard. They were anomalies, wrinkles in the system that could not be ironed out. I wondered, as I began my investigations, what I would find at the end of this story: a monster, who carried out sadistic attacks on some of the most vulnerable members of society? Or was there truth to the hoary adage "nobody knows what goes on behind closed doors"?

The police can often struggle with the unusual or unnatural, and serial killers can be harder to catch because their behaviour is more difficult to understand. Their need to kill can appear irrational, random and impulsive.

Since the Victorian era, police have been trying to turn detective work from an art form into a science in order to catch such killers more quickly. But part of detective work will always rely upon intuition and a sharp eye.

Stephanie Davies was not the only person who believed a serial killer was at work in Cheshire in the nineties. Christine Hurst, the coroner’s officer who dealt with the Wilmslow killings at the time, was also convinced the murders were the work of a single offender. Her warnings to the police would go unheeded.

The Wilmslow Killings

That particular Saturday lunchtime in Gravel Lane, Wilmslow, was much like any other. Cars trundled to the shops, children kicked balls in the nearby playing field, and just up the road, the tall, kindly figure of Howard Ainsworth could be seen taking advantage of the spring weather to potter about his garden.

He was looking after his wife, Bea, aged 78, who had a tummy bug. It was Saturday, 27 April, 1996: a time when Oasis and Blur were battling it out in the charts, and Princess Diana and Prince Charles were in the process of getting divorced. That day, Howard had been spotted in the garden, laughing and joking with the neighbours, talking about nursing his wife.

The next day, two uniformed police officers would enter their home — after being alerted their curtains had remained drawn all morning — and found them dead in their bedroom. Bea was on the right-hand side of the bed with a pillow on her face. Her nightie had been yanked up to her hip to expose her pubic area. Her head had been repeatedly bashed with a hammer. Somebody had stabbed a kitchen knife into her forehead.

Next to her was Howard, aged 79. His head was covered by a clear polythene bag which was spattered in fine droplets of blood. The bag sat on his head, cone-shaped, like a ceremonial hood from some forbidden religion. His right leg was crossed over his left. His left arm was trapped awkwardly under his body. His pale-blue pyjamas contained barely a spot of blood.

This was the first, and perhaps most obvious, clue which stuck out for Davies during her review many years later. How could Howard have killed his wife by smashing her skull repeatedly with a hammer so that blood landed on the bed, headboard, the bedroom walls – everywhere, except for Howard's own hands, face and body? There was no evidence he changed his clothes after the murder.

Then there was a hammer in the sink – a murder weapon which had been washed clean. Surely, Davies thought, this had more in common with an offender trying to get away with a murder, rather than a person about to take their own life. Why would Howard care about washing down the murder weapon?

The next issue she had was the strange positioning of his body. Both the coroner’s officer at the time of the deaths — Christine Hurst — and Stephanie Davies, saw evidence that he had been moved after his death, by person or persons unknown. His arm and hand was trapped under his body, as if somebody had picked him up and put him down on the bed. There were sleeping pills next to Howard on the bed, yet the toxicology came back negative. He had decided to make his death more painful by using only a bag — rather than the tablets and the bag. Odd, to say the least.

But perhaps one of the most compelling clues of all was the injuries which Howard had sustained to his lips. His lips were bruised. The pathologist at the time could not explain them. In fact, he notes in his report that the suicide method that Howard apparently chose could not explain those injuries: injuries far more common when a hand is clamped over the mouth in order to suffocate a person.

In amongst all that puzzling evidence was a suicide note. It was purportedly written by Howard, claiming that it “looks as tho our lives have gone”. How so?

Howard explained that Bea’s stomach bug had destroyed their quality of life. This was despite a GP having visited their home that very week to say that Bea was suffering from a bout of gastroenteritis which would clear up in 24-48 hours.

And yet Howard, said the police, had decided one evening to murder his wife — because of her tummy bug. It made little sense to the coroner’s officers. But lacking a suspect, Cheshire Police felt Howard being the killer best fitted the evidence they had. They decided that Howard's suicide note, along with his belief in euthanasia, pointed towards him being the killer.

The story of the Ainsworths might have ended there. But then, three years later, a few streets away from where Howard and Bea had lived, a second elderly couple were found dead in their bloodstained bed, lying side by side in their nightclothes, bodies ripped and torn, the woman’s nightdress yanked up to expose her pubic area, a pillow left on her face.

This time the police suspected a killer was on the loose. And they launched a hunt to catch him…

The Hunt for the Silver Killer, by David Collins, is available on Amazon and at all good bookshops.

Like the blur on the back of a book, but much longer and by the author of the book. Makes me want to read more!

That is scary stuff. I lived in Wilmslow a few years earlier than these “suicides”, and I do remember them being reported at the time. I will definitely be ordering a copy of the book.