The tragedy of Crompton Lodge

'They always say if you have nothing at all, at least you’ve got a home to go back to. Now I’ve got no home, what have I got?'

By Mollie Simpson

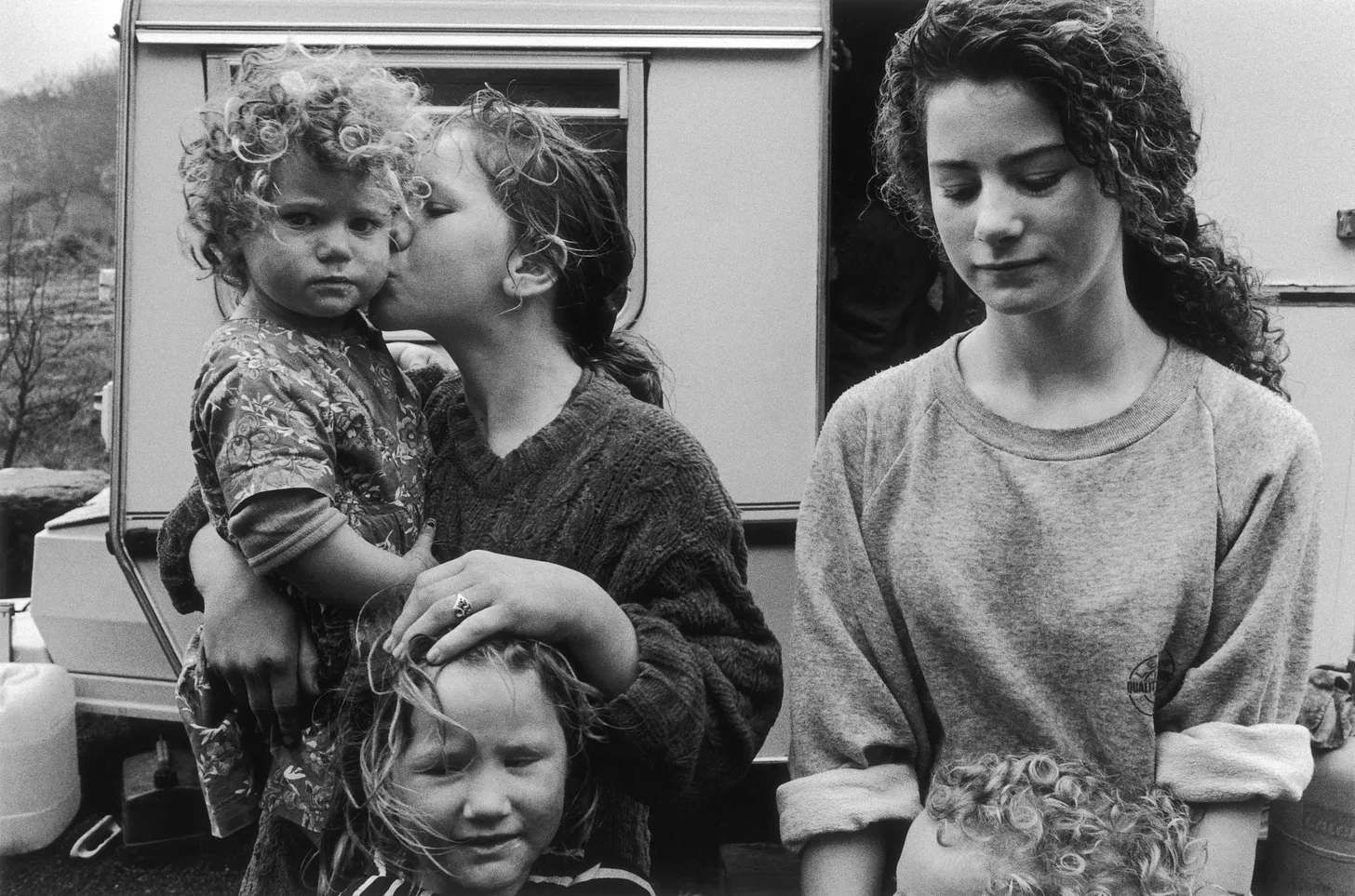

A few years ago, I met the Wards, a Gypsy and Traveller family, to understand the issues facing the community when so much media coverage that surrounds them is concerned with crime and violence. In the summer of 2021, Tommy Ward Senior, a skinny, self-assured man in his late 50s, invited me on a walk around Crompton Lodge, a sprawling caravan park tucked away near a busy road and a vast country park in Farnworth, where he and his family had lived for nearly 20 years. Bolton Council own and manage the site, and according to the Bolton News, nine families lived on the site, each having their own separate, self-contained plot.

Tommy showed me his home, which was a model of tidiness and coherence. Outside, it was a different story. There was litter piled up by the road, cracked leather sofas and abandoned bike wheels. Small metal spikes stuck their heads out of the concrete. “That could have been there for months,” Tommy said at the time, gesturing at a shed filled with debris on another tenant’s plot of land. “And nobody knows what's in it. Because it's none of our business. We've got no business on that plot. So we get judged for something we haven’t done.”

It’s now the summer of 2024, and a legal battle has been playing out between the tenants of Crompton Lodge and Bolton Council. The result will decide whether the family can stay together, or will be broken apart. In late June, the council informed the tenants that it would be making an application to the Magistrates Court to grant permission for a closure order on the site. If granted, this would allow the council to prohibit anyone from accessing the site without prior authorisation.

The council promised the tenants that they would be relocated into temporary accommodation, yet it cannot guarantee that the tenants will be able to stay together, or that their children will be able to attend the same schools after the move. Among the options the council has offered is a one-bedroom flat above a chip shop in Little Lever. “I’ll die if I have to leave my family,” Kath Ward Senior says. “All my grandchildren — I’ve got 29 — and my family’s never left me, even when they’ve got partners and their own children. Do you know what I mean? They follow you everywhere. [The council] just want to break us apart, and they break my heart.”

Bolton Council leader Nick Peel said in a statement that the decision not been “taken lightly” but that the council had “reached a point where it is no longer possible to safely maintain and run this site”. A long list of allegations was published by the Bolton News, and BBC Manchester described “an unruly caravan site plagued by guns, drugs and violent crime”. The articles read like a rap sheet. A council officer was attacked while on duty. Firearms were found in the toilets. Stolen cars were retrieved from the site. Police officers were verbally abused.

My interest in the case isn’t whether the allegations are true, but whether the decision to relocate the tenants is fair. In Courtroom Six of Manchester Magistrates Court, on a humid afternoon on Tuesday 2 July, one of the tenants posed a question: if an offence was committed in a cul-de-sac, or a council estate, would you shut down the whole council estate? Or would you convict the individuals responsible?

‘They never gave me the chance to be something’

Tommy Ward Senior has mostly stayed away from the court proceedings. He has previously suffered from two heart attacks and a hernia, and thinks it has something to do with stress. His children have been through hard times in their own lives, including burying their own children, various suicide attempts and a cancer diagnosis. Compared to when we met three years ago, the Tommy Ward Senior that I meet today is different, harder and easily frustrated.

The day before the trial, we’re driving around Ancoats, where Tommy spent part of his childhood on a Gypsy site and where his children were baptised. He points out the Catholic church where he worships and a convent he visits for religious guidance, driving cautiously as he goes. “I’m sorry if I’m driving too slow for you,” he says. “I don’t like to give the police any opportunity to stop me.”

We reach a red traffic light. Driving around the old haunts of his childhood seems to bring up painful memories: when he was refused an education on account of being a Traveller; when he made friends with the settled community, who he hoped would teach him to read and write. They never did, and Tommy eventually left these friends behind. He’s suspicious of authority, and blames the government for discriminating against him throughout his life. “I would truly say with my heart and soul, the government mentally scarred me,” he says, looking straight ahead. “They never gave me a chance to be something.”

‘They have thrown the towel in’

Back in the courtroom, Mr Scott Tuppen, a softly-spoken Welsh barrister, is speaking on behalf of the tenants at Crompton Lodge. He says there are ways to reduce criminality on the site without getting rid of all the tenants, some of whom have no criminal record. “There is a whole raft of options available to the local authority that have not been considered,” he says in his closing statement. “They have, in essence, thrown the towel in.” Bolton Council says it attempted “several multi-agency interventions”, but this did not achieve an impact in crime reduction.

In the waiting room, a member of the defence team asks Eileen Ward if she’s happy to give evidence as a witness, and when she says yes, he asks her again if she’s sure. She walks up to the stand confidently, wearing a white turtleneck and smart trousers. None of the evidence of the criminality at the site presented to the court is attributable to her, but she still faces losing her home.

Eileen’s clean record won’t support her plea for the council to reconsider the closure order, so she has to use a different tactic. For the judge to approve Bolton Council’s application, she has to be satisfied that there has been antisocial behaviour or disorder at the site in the past, that it is likely to recur again, and that the order is necessary to prevent it recurring. There is plenty of evidence that antisocial behaviour has occurred, so the tenants have just one glimmer of hope: to prove that the order isn’t necessary.

Eileen tells the court about her son, Nico. “He’ll be the first boy out of our whole family to go to high school,” she says. “I am proud of him. He’s a really great lad, he can go so far.”

Would Nico struggle to attend the same high school, if he and Eileen were relocated into temporary accommodation? Mr Tuppen asks.

“100%. Nico wouldn’t be continuing on to school, it’s too far, Nico wouldn’t be able to go there,” Eileen says. Later, she says: “Look, my son could be the biggest barrister in the world, he could be defending one of you someday. If he goes to high school, he could be something.”

Mr Tuppen says a lot of allegations around criminality had been made. What did she have to say about that?

“It’s not our fault,” Eileen says. “We as residents can’t control what goes on around us.”

“How would you propose the council stop the criminality?” he asks.

Eileen replies that she wanted the council to improve security at the site. There is no gate or fob entry required to access the site, which many of the residents blame for the rise in criminality. She said she acknowledges that things had gone wrong at the site, but that it’s “the police and council’s responsibility to stop it happening”.

After the defence finishes presenting its case, Mr Peter Marcus, the prosecuting barrister working on behalf of Bolton Council, argues that while Eileen was not responsible for any of the crimes, that she is still complicit, and is happy to let it continue.

“You’re clearly happy for your children to live in a site where firearms are found,” he says. “And when they are found, you do nothing about it.”

“I don’t know what you want me to say,” Eileen says, suddenly brittle and defensive. “Would I like the site to be more secure? Yes. But that’s the police and the council’s responsibility.”

Mr Marcus shifts into quickfire mode.

“It’s always someone else’s fault if something goes wrong or if you commit a crime.”

“No.”

“It’s always the council’s fault if there’s a problem with the site.”

“No.”

“Let me just clarify, you are not accepting the council’s offer, whether it’s temporary or permanent accommodation?”

“No.”

“Well, if the council make you an offer for a new home and you put up these goalposts and say I won’t have that because it’s not near my kid’s school, you’re not really playing the game, are you?”

“It’s not a game for us, sir,” Eileen says, wiping away tears. “This is our home.”

‘Bolton Site is gone’

Outside of the courtroom, Kath, Lizzy and Eileen Ward sit with their knees to their chest, looking out of a big, glass window facing a construction site. Mr Tuppen has been cautiously managing their expectations while also indicating that there seemed to be some hope. He says it’s likely that a closure order will be granted, but seems hopeful that Bolton Council will be amenable to adding certain conditions to the order, such as improved security, regular meetings between council officers and residents, and giving authorisation to certain residents to return to the site. Eileen bites her nails anxiously. She hasn’t managed to stop crying.

I ask about solutions and I hear that an offer arrived from Bolton Council at some point earlier this week. The local authority had said it would find a new Gypsy and Traveller site for the families, and pay the first eight months of rent, if they left Crompton Lodge. A spokesperson for Bolton Council tells us that the tenants refused the offer.

Is it stubbornness? A tentative hope that they can find a way to stay at Crompton Lodge? Or a refusal to accept the reality of what’s happening? Having spent days listening to both sides, I can see how challenging the situation has become, but it feels hard to get away from the feeling that a group of people, some of whom have done nothing wrong, are collectively being held responsible for the criminal actions.

For Eileen, the reasons are more emotional. “This is my home,” she explained when Mr Tuppen questioned her on day two of court proceedings. “I don’t just lose my bricks and mortar, I lose my memories of my little boy who I buried in the ground here.”

In response to our questions about the local authority’s accommodation offer, a spokesperson for Bolton Council told us:

“The council has offered support to residents in the form of a temporary accommodation offer. It has also offered support with deposits and rent advancements should the residents source private or public pitches or other private accommodation themselves. We also offered to help support sourcing alternate accommodation. This is consistent with our homelessness offer to those we owe a duty to. We have also since made amendments to the offers of accommodation in response to requests from the tenants on their family makeup and location, the requests facilitated by the Irish Community Care. These like previous offers have all been turned down. All of the accommodation offers were in Bolton, several close to schools the children go to.”

On Wednesday 3 July, we watch as District Judge Lucy Hogarth addresses the court from a large, polished brown table. She’s decided to make the closure order. The precise conditions will be decided by Bolton Council. She goes on to describe the residents as “commendably frank” and says she has thought hard about how best to balance “the very strong feelings of the residents with the very powerful evidence presented by the local authority.”

“It’s become clear that for some time Crompton Lodge has become a safe haven for criminals, some of whom are connected to the residents, some of whom are not,” she says. “It’s my hope, though I have no power to direct it, that the local authority does find some way to let you back to your homes. However, I cannot see that is realistic at the moment without some further engagement, and without staff and contractors being allowed to work safely on the site. My verdict now leaves that in the hands of the local authority. It is likely in the short term that no one will be allowed to return to the site.”

The court usher asks us all to rise as the judge leaves. The doors reopen and the waiting room fills with people. With no indication of whether the residents can return to Crompton Lodge to retrieve their belongings before leaving, or whether this marks the end, a sense of panic sets in.

“I need to get my son’s medication,” a tenant tells Mr Tuppen. “He’s on medication for ADHD. He regularly visits Bolton Hospital. They have to let me go in.” Lizzy and Kath Ward repeatedly ask what’s happening. No one seems to know.

Mr Tuppen says it might help to make a list of all the names of the residents at the site to help the council make their decision on who is allowed back, and who isn’t. I hand my notebook and pen to Tommy Ward Senior. “I can’t read or write, love,” he reminds me.

Kath and Eileen grab the notebook from his hands and sit in a corner, writing as many names as they can remember. Eileen starts sobbing. A few minutes later, Mr Tuppen takes the list and disappears inside the courtroom.

Fifteen minutes later he returns with a different piece of paper. Written on it is the council’s decision. Bolton Council has decided it is prepared to give the residents permission until 10am on Monday 8 July to return to the site to retrieve belongings, remove property and make other arrangements. This gives the tenants five days to leave.

Kath, who until now has been strong for her sister Eileen, starts to get emotional. “They always say if you have nothing at all, at least you’ve got a home to go back to. Now I’ve got no home, what have I got? I’ve got a black bag on my back. That’s what I’ve got. A black bag,” she says, on the verge of tears.

“There’s no Bolton site anymore,” Eileen replies, her head in her hands. “Forget Bolton site, it’s gone.” Kath calls her sister Lizzy while sitting on the floor near a power outlet where she’s charging her phone, sobbing and rubbing her forehead, explaining what’s happened.

On Monday 8 July, news articles emerged in the local media explaining that Bolton Council succeeded in its application for a closure order. Police watched as the residents left the site, quietly and without resistance. “We did not want to cause a scene,” Eileen Ward told the Bolton News.

That same day, an illegal encampment appeared in playing fields in Breightmet, a working-class area of Bolton. Two caravans and two cars were spotted setting up home. A resident named Margaret Doran told the Bolton News that they had come from Crompton Lodge and more of them would be coming. "This is the best spot we could find, we are not leaving Bolton, we have schools and the doctors here,” she said. "People have been welcoming, they have asked if we would like to use their facilities.” A local councillor said he didn’t know anything about them, just that they’d been asked to move on.

Great article Mollie, a beautifully written portrayal of the kind of discrimination and persecution faced by gypsies and travellers in the UK and elsewhere. Why should they be held responsible for their neighbours' anti social behaviour when the rest of us are not? It is a very old and community driven way of living and it would be a tragedy if all camp-sites were to be closed with the only alternative accommodation a flat above a chip shop.

In England's myriad societal Venn diagrams, where the overlaps are usually simply 'crime!,' or bureaucratic civic paperwork, the rest of the picture is often invisible. This is brilliant work.